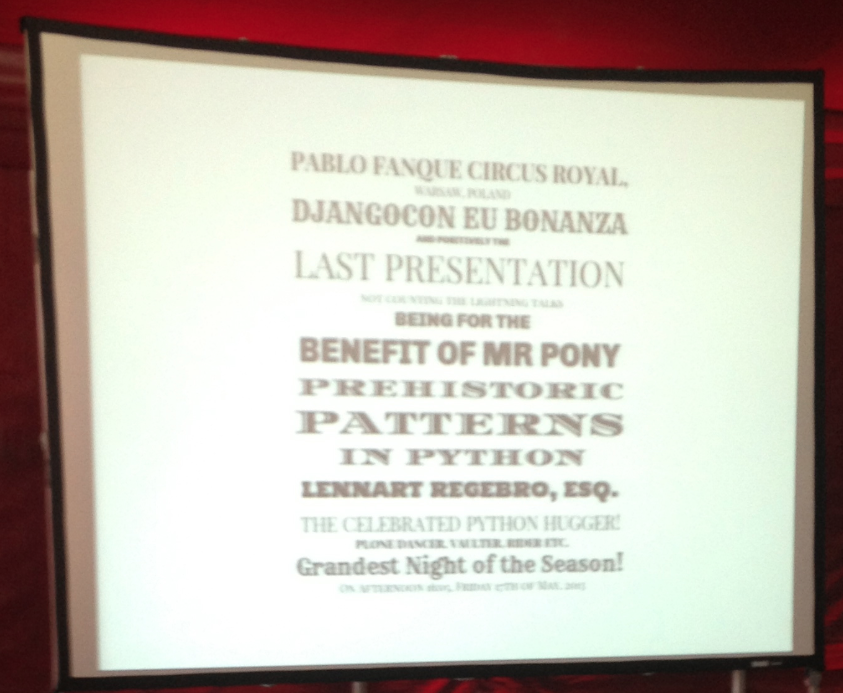

Prehistorical Python: patterns past their prime - Lennart Regebro¶

Dicts¶

This works now:

>>> from collections import defaultdict

>>> data = defaultdict(list)

>>> data['key'].add(42)

It was added in python 2.5. Previously you’d do a manual check whether the key exists and create it if it misses.

Sets¶

Sets are very useful. Sets contain unique values. Lookups are fast. Before you’d use a dictionary:

>>> d = {}

>>> for each in list_of_things:

... d[each] = None

>>> list_of_things = d.keys()

Now you’d use:

>>> list_of_things = set(list_of_things)

Sorting¶

You don’t need to turn a set into a list before sorting it. This works:

>>> something = set(...)

>>> nicely_sorted = sorted(something)

Previously you’d do some_list.sort() and then turn it into a set.

Sorting with cmp¶

This one is old::

>>> def compare(x, y):

... return cmp(x.something, y.something)

>>> sorted(xxxx, cmp=compare)

New is to use a key. That gets you one call per item. The comparison function takes two items, so you get a whole lot of calls. Here’s the new:

>>> def get_key(x):

... return x.something

>>> sorted(xxxx, key=get_key)

Conditional expressions¶

This one is very common!

This old one is hard to debug if blank_choice also evaluates to None:

>>> first_choice = include_blank and blank_choice or []

There’s a new syntax for conditional expressions:

>>> first_choice = blank_choice if include_blank else []

Constants and loops¶

Put constant calculations outside of the loop:

>>> const = 5 * a_var

>>> result = 0

>>> for each in some_iterable:

... result += each * const

Someone suggested this as an old-dated pattern. You can put it inside the loop, python will detect that and work just as fast. He tried it out and it turns out to depend a lot on the kind of calculation, so just stick with the above example.

String concatenation¶

Which of these is faster:

>>> ''.join(['some', 'string'])

>>> 'some' + 'string'

It turns out that the first one, that most of us use because it is apparently

faster, is actually slower! So just use +.

Where does that join come from then? Here. This is slow:

>>> result = ''

>>> for text in make_lots_of_tests():

... result += text

And this is fast:

>>> result = ''.join(make_lots_of_tests())

The reason is that in the first example, the result text is copied in

memory over and over again.

So: use .join() only for joining lists. This also means that you

effectively do what looks good. Nobody will concatenate lots of separate

strings over several lines in their source code. You’d just use a list

there. For just a few strings, just concatenate them.

That’s the nice thing of Python: if you do what looks good, you’re mostly ok.